Weekly Picks – April 13, 2025

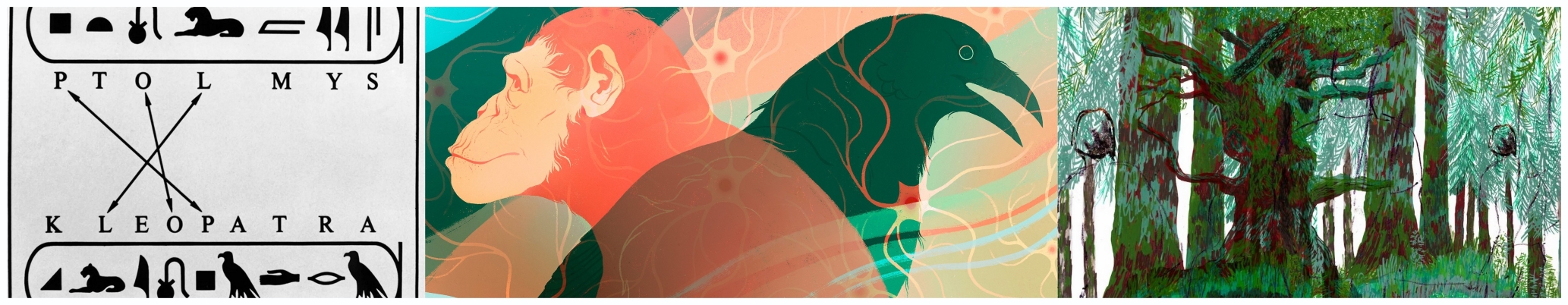

Credit (left to right): Public Domain; Samantha Mash; ariel rosé

Credit (left to right): Public Domain; Samantha Mash; ariel rosé

This week’s collection:

- Liminal Border Situation | Eurozine

- Noblesse Without Oblige | Dissent

- Friends with benefits? The country still in thrall to the Wagner Group | 1843

- The lonely life of a glyph-breaker | Aeon

- Intelligence Evolved at Least Twice in Vertebrate Animals | Quanta Magazine

Plus, for Astronomy aficionados:

Find out how these lists are compiled at The Explainer.

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

1. Liminal Border Situation | ariel rosé

“The Forest is a society with ‘Mother Trees’. Ecologist Suzanne Simard describes them as ‘hub trees’ sharing excess carbon and nitrogen through a mycorrhizal network – like a world wide web of messages about possible danger or good light spots. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s theory of rhizomes and roots also comes to mind. The non-linear network that connects us with plants and animals makes perfect sense here. Philosopher Éduard Glissant noticed that roots ‘make the commonality of errantry and exile’, which might seem an oxymoron to us. But there is a point to it, ‘for in both instances roots are lacking’.

Refugees, exiles, immigrants and nomads abandon their roots. They abandon the graves of their ancestors and wander rootless. Yet, ‘the tale of errantry is the tale of Relation’, adds Glissant. Refugees are a moving element related to the place and its inhabitants. They make a new special entity. The border they wish to cross is a construct of the Westphalian world order, which Carl Schmitt deemed Ius Publicum Europaeum (European public law), relatively fresh and not sacred, not delineated by gods. Achille Mbembe calls for a borderless globe, for a freedom of mobility. Refugees who lose their lives attempting to cross the Polish-Belarusian border are cut off from their families in Africa or East Asia. Who will visit their graves? […]

In 2021 President Alexander Lukashenko in collusion with Vladamir Putin started handing out visas to refugees and immigrants from Iraq, Afghanistan, and other Middle Eastern and African countries. Belarusian authorities pushed for their transfer across the border to Poland, Lithuania and Latvia, weaponizing refugees against the European Union, thus waging hybrid warfare. Lukashenko’s government knew that an increasingly right-wing-leaning Europe wanted to limit immigration. And his immigration policy was direct retaliation to sanctions that the EU had imposed after the rigged Belarusian presidential elections in 2020 and repression of the opposition.

In August 2021, when a group of refugees from Afghanistan appeared at the border near the village of Usnarz Górny, the Polish right-wing, anti-immigration government, led by the Law and Justice party (PiS), was still in power. The refugees, who weren’t allowed to apply for asylum, were pushed back by the Polish guards on the one side and then again by the Belarusian guards on the other, stuck in the Forest without food, water or shelter.

Shortly thereafter, the Polish government introduced a provisional state of emergency in its border regions with Belarus. No one other than residents were allowed to stay in the designated zone. Any assistance given to refugees became punishable. In January 2022 the PiS government began building a razor-wire fence along the border, which is now approximately 180 km long, 5.5 metres high and cost PLN 1.6 billion (350 million euros) – the money coming from an EU budget for road construction. Poland used money de facto from the European fund despite the objection of Ursula von der Leyen. The state of emergency, first scheduled until 1 March 2022, was extended until the end of June. And the current government under Donald Tusk has since reintroduced a closed zone along the border.

In 2022, and again in August and November 2023, I helped refugees in the Forest from the base camp of volunteer group Grupa Granica (Border Group) and at a seminar organized by Researchers at the Border. I spoke mainly with those who help at the border: the activists, volunteers, residents and visitors, who do so from the kindness of their hearts, and are exhausted, traumatized and harassed. It became clear to me that the work they do should be done by the state, which has instead built a fence on which people and animals die.”

2. Noblesse Without Oblige | Vanessa Ogle

“Over the past eight years, a series of major document leaks has shone a spotlight on tax havens and their users. The Panama Papers, made up of 11.5 million documents from the offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca, broke in 2016. Next came the Paradise Papers in 2017, a trove of even more material, mostly from the Bermuda-based law firm Appleby and two other offshore corporate services providers. The Pandora Papers, published in October 2021, constituted the largest and most comprehensive such leak yet. Several earlier, smaller leaks—including the Swiss Leaks in 2015 (from the Swiss subsidiary of the British multinational bank HSBC) and Lux Leaks in 2014 (detailing tax arrangements for multinationals devised by the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers and the Luxembourg government)—had garnered less publicity but likewise revealed the shameless activities of lawyers, accountants, bankers, and their clients. […]

Given such wrongdoing among a sliver of extremely wealthy and influential individuals, why, after a couple of weeks of public attention, does the problem of tax evasion fade from view so quickly? In Offshore, Brooke Harrington, a sociologist at Dartmouth College, suggests an answer to this question. Part of the problem, she contends, is the culture of secrecy that pervades tax havens and other offshore jurisdictions. Most often, we simply forget that tax havens exist. This is not a bug but a feature of the system, designed by the politicians, lawmakers, and professionals who enable tax avoidance and evasion.

Harrington’s contention is that if these shenanigans of the super-rich were less shrouded in secrecy, people would be more outraged. That is probably true. Secrecy doesn’t just help rich people dodge the tax man, but also to keep the most unfair and unsettling aspects of widespread tax avoidance and evasion out of public view. Harrington cites recent findings by economic psychologists showing that most people vastly underestimate the extent of inequality in their countries—in the United States, by as much as 42 percent. Since the 1960s, offshore capitalism has quietly helped transform the global economy by pioneering financialization, facilitating elite impunity, and supporting the accumulation of ever greater intergenerational wealth, all while shielded from outside scrutiny. […]

One reason for the prevalence of corruption and related crimes in offshore tax havens is that many such territories never had an opportunity to develop a healthy and stable civil society, social fabric, or political system. The establishment of offshore businesses in the Caribbean happened mostly while islands such as the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, and the Caymans were still under British rule; in fact, many tax havens forewent independence altogether, to benefit from the impression of stability and continuity that British dominion signaled to outsiders looking to park their money. White colonial elites in colonies-turned-tax-havens were often directly involved in registering companies and trusts and in passing the laws necessary to beef up the credentials of the emerging havens. In places that did pursue independence, such as Mauritius and the Seychelles, the turn to offshore capitalism occurred in moments of desperation, when, after gradually scaling down aid and other support, colonial overlords officially departed, leaving an economic, political, and social vacuum that was ripe for outside exploitation.”

3. Friends with benefits? The country still in thrall to the Wagner Group | Tom Gardner

“Unlike Congo 80 years ago, [the Central African Republic] has nothing so valuable to outside powers as nuclear metals. Despite its ample reserves of gold, diamonds and timber (and small deposits of difficult-to-extract uranium), this country, which is roughly the size of France, has always been a geopolitical backwater. It is landlocked, and surrounded on all sides by perennially troubled neighbours. The sleepy tributary of the Congo river on whose banks Bangui sits is navigable by boats only part of the year. Its geographical isolation meant CAR was one of the very last patches to be claimed during the “scramble for Africa” in the late 19th century.

A century ago the territory which became CAR was little more than a way station, a bend in the Ubungi river used for ferrying plunder from the continental interior to the coast. One French writer dubbed it a “phantom”, a “country which doesn’t exist”. Even Barthélemy Boganda, the first leader of the newly autonomous CAR in the late 1950s, harboured serious doubts about its prospects as an independent country.

Yet since Wagner forces arrived in 2018, officially as “military instructors” sent by Russia to help build a national army and beat back rebels, CAR has attracted more attention than ever before from the outside world. Some of this has come from journalists, lured by the prospect of encountering Prigozhin’s shadow army first-hand.

Western governments, too, are keeping an eye on goings-on here. Long after they were forced to give up their empires, many outside powers still see Africa primarily as a geopolitical chessboard. Wagner forces are constructing a base in CAR, intended to host 10,000 troops by 2030. Western diplomats worry it will be used as a launch point for projecting Russian power across the continent: in Congo, west Africa, the strategically important Sahel. CAR’s leaders are keen to exploit its newfound significance.”

4. The lonely life of a glyph-breaker | Francesco Perono Cacciafoco

“I was pursuing the dream of all historical linguists and glyph-breakers: I wanted to return their own voices to peoples from the past by being able to read the written documents they’d left behind. That is what scholars who study the history and the evolution of writing systems do and dream – that is their path.

That path is mercilessly lonely. Full of bumps and disappointments, generally characterised by bitter self-assessment and self-reflection, with a lot of regrets. A glyph-breaker’s life can become very dark (or bizarre – it depends on how they take it), especially in academia. […]

Despite the fact that the decipherment of ancient writing systems is considered a fascinating endeavour and that people are episodically attracted by news involving archaeological discoveries and the interpretation of ancient scripts, what today can be called language deciphering isn’t properly a recognised academic discipline, doesn’t belong to any specific field (a bit of linguistics, a bit of philology, a bit of cryptology, a bit of grammatology, etc), and isn’t systematically taught or practised in universities.

If somebody deciphered a previously undeciphered writing system for real today, many individuals and institutions would jump on the bandwagon of that glyph-breaker. One or more universities would claim that the new ‘genius’ is affiliated with them (perhaps, the scholar studied there 20 years before the discovery or was a neglected part-time lecturer whose contract wasn’t renewed) and top-tier academic journals would enter a fierce competition to publish the findings. The press would fill pages and pages for 48 hours, only to shunt the story to oblivion on day three. […]

Once a writing system is finally deciphered, a new world opens before our eyes. Before that, we knew a civilisation that used a script we weren’t able to read only through its material culture, archaeological findings and remains or external historical sources. After we’re able to read the writings of that civilisation, a whole new treasure trove of information is readily available to us. Deciphering languages is, therefore, not only the archaeology of writing, but the only discipline that allows us to discover ancient peoples through their own words, by reading the documents they left behind.”

5. Intelligence Evolved at Least Twice in Vertebrate Animals | Yasemin Saplakoglu

“Humans tend to put our own intelligence on a pedestal. Our brains can do math, employ logic, explore abstractions and think critically. But we can’t claim a monopoly on thought. Among a variety of nonhuman species known to display intelligent behavior, birds have been shown time and again to have advanced cognitive abilities. Ravens plan for the future, crows count and use tools, cockatoos open and pillage booby-trapped garbage cans, and chickadees keep track of tens of thousands of seeds cached across a landscape. Notably, birds achieve such feats with brains that look completely different from ours: They’re smaller and lack the highly organized structures that scientists associate with mammalian intelligence.

“A bird with a 10-gram brain is doing pretty much the same as a chimp with a 400-gram brain,” said Onur Güntürkün, who studies brain structures at Ruhr University Bochum in Germany. “How is it possible?”

Researchers have long debated about the relationship between avian and mammalian intelligences. One possibility is that intelligence in vertebrates — animals with backbones, including mammals and birds — evolved once. In that case, both groups would have inherited the complex neural pathways that support cognition from a common ancestor: a lizardlike creature that lived 320 million years ago, when Earth’s continents were squished into one landmass. The other possibility is that the kinds of neural circuits that support vertebrate intelligence evolved independently in birds and mammals. […]

Intelligence doesn’t come with an instruction manual. It is hard to define, there are no ideal steps toward it, and it doesn’t have an optimal design. Innovations can happen throughout an animal’s biology, whether in new genes and their regulation, or in new neuron types, circuits and brain regions. But similar innovations can evolve multiple times independently — a phenomenon known as convergent evolution — and this is seen across life. […]

What are the building blocks of a brain that can think critically, use tools or form abstract ideas? That understanding could help in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence — and help improve our artificial intelligence. For example, the way we currently think about using insights from evolution to improve AI is very anthropocentric. “I would be really curious to see if we can build like artificial intelligence from a bird perspective,” Kempynck said. “How does a bird think? Can we mimic that?””