Weekly Picks – May 11, 2025

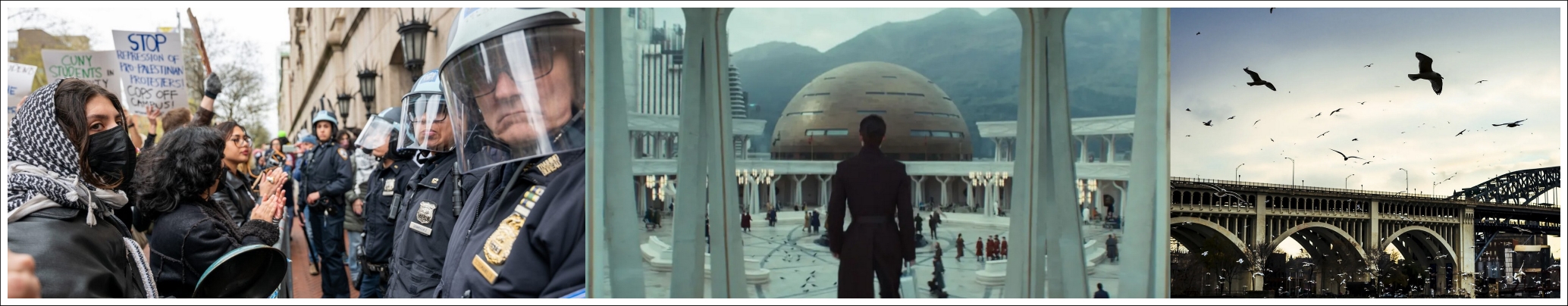

Credit (left to right): Spencer Platt/ Getty Images; Lucasfilm/ Disney+; Getty Images

Credit (left to right): Spencer Platt/ Getty Images; Lucasfilm/ Disney+; Getty Images

[Update: this is the last ‘Weekly Picks’ post published to the blog. Additional notes here.]

Please note: I will be unable to share ‘Weekly Picks’ on May 18 and 25 due to a packed schedule. ‘Weekly Photo’ posts will continue uninterrupted.

This week’s collection:

- Doing Their Own Research | New York Review of Books

- The Right to Be Hostile | Boston Review

- The burning river that fuelled a US green movement | BBC

- The path to the Death Star is paved with lies | Salon

- The Fight for the Soul of Video Games | The Nation

Find out how these lists are compiled at The Explainer.

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

1. Doing Their Own Research | Hari Kunzru

“If you have ever found your way to the part of the Internet where people “do their own research,” you may have encountered the art of David Dees. He once freelanced as a commercial illustrator for clients including Disney and Sesame Street, but his career faltered in the mid-Aughts after he contracted a serious illness that he attributed to cadmium poisoning from paint. After a spell in Sweden, during which he came to believe he was being targeted by sinister forces he identified as “Zionists,” the CIA, or agents of the agrochemical company Monsanto, he became a recluse in rural Oregon, treating his ailment with meditation and Reichian electrical “frequencies” as he produced a wildly popular body of baroque and frankly paranoid “political art” (his own term). Dees’s instantly familiar Photoshop aesthetic is lurid and hectic to the point of absurdity. Politicians become bulging-eyed grotesques. State storm troopers menace crying children. Black helicopters hover in the air. Each frame is busy with visual violence, batteries of jabbing needles, rivers of glowing radioactive sludge.

Dees died of cancer in May 2020, just as the pandemic was getting underway. Consequently he made very few images of what surely must have felt like the end of days, the sum of all his fears. His work defines what might be called the New Weird Fusionism, a successor ideology to the old Fusionism that powered the Republican revolution of the 1970s and 1980s. That Fusionism, which emerged from William F. Buckley Jr.’s circle at the National Review, was a union of social conservatism with political and economic libertarianism, and it proved to be a recipe for electoral success. The New Weird Fusionism combines ideas from the conspiracy cultures of the Christian right and the countercultural left, and it too has forged an electoral coalition, fueling the populism that has brought Donald Trump to power for a second time. […]

Take this pervasive culture of magical thinking, add in fears of an enemy’s hidden hand, dissolve the mixture in the radically flattened media environment of today’s Internet, which rewards provocation and reinforces bias, and a phenomenon like QAnon becomes not just comprehensible but almost inevitable. Its promise that the evil child abusers of the deep state will imminently be brought to justice is legible as a version of the “paradigm shift” of conspirituality. This is a mode common to Christian millenarianism (the empire is satanic, Jesus is coming), New Age spirituality (this is the dawning of the Age of Aquarius), and believers in the transhumanist “singularity,” the point of technical acceleration beyond which the future is impossible to predict or control. The New Weird Fusionism mobilizes all these beliefs, allowing participants to role-play through our polarized present as superior spirits experiencing the thrill of the collapse of the established order of things. Becoming “aware” or “awakened” or merely “woke” is a motor for fundamental transformation, a shift in personal consciousness that is also a shift in objective reality. If you “follow the white rabbit,” as QAnon urges, you will find a hidden truth so fiendishly concealed that it cannot be understood without a huge common effort. Now you are part of something. Something big.”

2. The Right to Be Hostile | Alex Gourevitch

“Over the last year and a half, American universities have rapidly destroyed the right to protest on campus. At the request of administrators, heavily armed police raided unarmed, nonviolent protesters opposing Israel’s war on Gaza. Encampments have been forcibly cleared, while extreme punishment has been used as a tool of intimidation. Some 3,100 students have been detained or arrested, and thousands more face severe university discipline—suspension, expulsion, and loss of degree.

More recently, the Trump administration has exacted even more suppression. First it suspended $400 million of federal funding to Columbia, conditioning its restoration on accession to a range of outrageous demands whose fulfillment, the administration alleges, is necessary to protect Jewish students and comply with Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Sixty other universities were subsequently threatened with the same shakedown. Since then, Columbia protester Mahmoud Khalil was disappeared, despite his possession of a green card; he was only the first. In response, several universities have adopted extremely restrictive speech codes and protest rules, developed new disciplinary procedures and task forces, ousted faculty, decimated whole departments, and imposed draconian punishments. Only when faced with something approaching a hostile government takeover have universities like Harvard started to fight back.

Many factors, in addition to moral cowardice and ideological agreement, help to explain why universities capitulated. Across the country, their budgets have grown increasingly reliant on federal funding, especially to support scientific research. The structures of university governance empower boards and presidents over faculty, students, and staff, while trustees, with deep ties to business and politics, typically have little connection to research and teaching or to the institution at large. Endowments are widely seen as indicators of prestige, not to be spent down to defend institutional integrity but constantly expanded through the cultivation of megadonors. Meanwhile, a vast class of administrators has ballooned over the last half century, rendering donor relations ever more transactional and student life both more consumerist and more surveilled. To top it off, many elite universities have forsaken institutional neutrality for an increasingly vocal social justice liberalism over the last decade, both in the messaging of campus leadership and in administrative meddling in speech and student affairs.

All this has left universities vulnerable to Trump’s attacks. Working in tandem with well-organized networks of “anti-antisemitism” advocacy groups, the administration is wielding antidiscrimination laws and “safetyist” rationales the right has spent years attacking to carry out the “counterrevolution blueprint” that Manhattan Institute senior fellow Christopher Rufo laid out in December, calling for purging universities and the federal government of “left-wing ideologies.”

How should we fight back against this new McCarthyism? And to what end? As teachers and students learn just how little control they have over campus, it is clear that we need not just a general defense of academic freedom but also a more specific and absolutist defense of the right to protest. A democratic society generally, and colleges and universities in particular, must protect the right to engage in public, disruptive acts—including those that feature open expressions of hostility to political views—even at the cost of some people feeling discomfort or even intense unease.”

3. The burning river that fuelled a US green movement | Ally Hirschlag

“By the late 1800s, Cleveland and the Cuyahoga had become a hub for the Industrial Revolution. Stradling says it started with steel mills towards the head of navigation (the farthest point upstream on a river where boats can travel, often defined by a dam or other physical barrier). The river made it easy for boats to transport ore. “Once the steel industry became established in Cleveland, all these other ancillary industries were good to have nearby,” he says.

With all of this steel production came excess chemicals and grease, says Stradling, and since there were virtually no environmental regulations at the time, a lot of it ended up in the river, along with raw sewage.

“We didn’t treat our wastewater, so anything that you flushed down the toilet was piped straight into the river,” says Adam Schellhammer, Mid-Atlantic regional director of the non-profit, American Rivers. Then, in the early 1900s amid World War One, industrialisation ramped up and the river pollution got worse. “With that uptick in manufacturing, these rivers were bearing the brunt of all that, and there were no restrictions on what went in,” says Schellhammer.

By the 1930s, the Cuyahoga had essentially become an open sewer, infamous for its foul smell and telltale sheen of oil slick. Unsurprisingly, the fauna that typically reside in and around the river steered clear, or died. “The Cuyahoga was a completely dead river for decades,” says Stradling. “There were no fish, no water fowl.” Those who lived nearby cautioned that if you fell in, you had to be rushed to the hospital.

And, occasionally, the massively polluted river burned.”

4. The path to the Death Star is paved with lies | Melanie McFarland

“Two years is not very long, especially when you suspect your time is running out. This is how much time the people of Ghorman have to wake up to the inevitability of their destruction — two years, which translates to eight episodes in “Andor” terms.

This is also how long it takes for the Empire to persuade enough of the galaxy to believe that 800,000 Ghorman citizens deserve to be displaced or eradicated. As Imperial Security Bureau (ISB) head Major Partagaz (Anton Lesser) mentions in “One Year Later,” the second season premiere, this is no easy task. Ghorman, Partagaz warns, is not without political power.

As for why that is, he doesn’t say. Instead, series creator and showrunner Tony Gilroy shows us, in what appears to be a tourism film, that Ghorman is a cosmopolitan fashion mecca reminiscent of Paris. People dream of visiting, and if not that, owning clothing made of its famous fabric, woven from fiber spun by spiders.

But the Empire needs a mineral in the planet’s soil that not even its people, the Ghor, know about. Hence, on faraway Coruscant, it dedicates a secret task force devoted to ensuring that when the time comes, the planet’s people won’t be able to get in its way, and that few will desire to help them.

This is where the Ministry of Enlightenment’s propaganda weavers enter the picture. […]

[Tony Gilroy:] “History has its own relevancy, and the repetition and the rinse and repeat of history is something that a lot of people don’t really seem to be aware of.”

Sure. Many speculative fiction writers say some version of this whenever people point out disturbing similarities in their shows and movies to current events. In the same way that 2016’s “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story” arrived in theaters just as the nation officially embraced the Dark Side, the first season of “Andor” debuted just in time to confirm that America was well on its way to becoming an autocracy.

Even back then, its writers didn’t have to consult dead tree pulp to recognize the ways the right-wing media has warped so many people’s views to a degree that the morally indefensible is acceptable.”

5. The Fight for the Soul of Video Games | Lewis Gordon

“In the 2000s, an ideological battle played out across the fictional cosmos of EVE Online. The MMORPG, which is set 21,000 years in the future, lets its players, alongside their friends and enemies across the Internet, explore a galaxy called New Eden. It is, at times, a tedious game, one premised on mining and trading in order to accrue capital and power, but players can circumvent all that by using real-world money to get ahead of their rivals. With little interference from its makers, the game became a site of fierce political debate and intrigue. Allegiances formed; factions rose and, inevitably, fell—Game of Thrones on a cosmic scale, involving tens of thousands of players at any one time.

On one side of EVE Online’s defining conflict was the Band of Brothers, a group of players who acquired powerful in-game enhancements using their own money rather than gathering resources the hard way. On the other side sat a poorer group of players called Goonswarm, who took umbrage with the rapacious techniques of their moneyed counterparts and launched a full-scale war against them. Eventually, the Goonswarm alliance claimed victory, a stunning coup accomplished via virtual espionage: Members infiltrated the private forums of the Band of Brothers, leaking information and launching stinging counterattacks—aided, late in the day, by the defection of the former BoB chairman, Haargoth Agamar. The defeat ultimately cost the Band of Brothers $6,000 in real cash.

In the world of video games, where protest mostly takes the form of negative user reviews and online complaints, stories of more sophisticated player organization and direct action catch the eye. For Marijam Did, author of Everything to Play For: How Videogames Are Changing the World, the showdown between the Band of Brothers and Goonswarm was a catalyzing moment: It broadened her horizons about what video games are capable of and offered a reflection of the world through a lens she was familiar with, namely that of class warfare.”