Weekly Picks – April 27, 2025

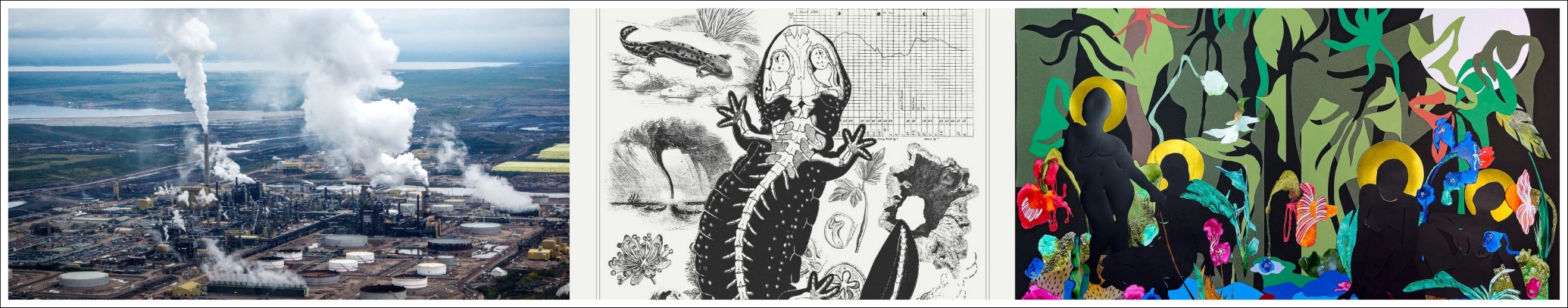

Credit (left to right): Ben Nelms/ Bloomberg via Getty Images; Mother Jones illustration/ Getty; Llanor Alleyne

Credit (left to right): Ben Nelms/ Bloomberg via Getty Images; Mother Jones illustration/ Getty; Llanor Alleyne

This week’s collection:

- Canada’s Oil Habit Is Wrecking Its Future | Jacobin

- The life of a dairy cow | Vox

- The Climate Movement Should Become a Human Movement | Hammer & Hope

- Fertility on demand | Works in Progress

- Anatomy of an Extinction | Mother Jones

- Borders May Change, But People Remain | Public Books

The Canadian federal election is scheduled to conclude tomorrow. I do not align with either major party, but reside in a riding where, at least this time, a strategic vote had to be cast (in a rather undemocratic first-past-the-post system). No one can predict the future, and platform commitments are often abandoned, but it is difficult not to assess the published policies of the two largest parties as regressive. Even though one is far worse than the other, both promise little to address the big existential issue of our time. I do not carry much hope even if the Liberals eke out a victory on Monday. Historically, it would represent one of the most striking turnarounds in public sentiment that we are likely to ever see. Politically, it will continue paradigms facilitating unsustainable growth and increasing inequality. You can dodge a bullet without jumping ahead.

Some perspectives on this fledgling democracy:

- Second Nature | 3 Quarks Daily

- What the Election Won’t Fix | The Walrus

Find out how these lists are compiled at The Explainer.

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

1. Canada’s Oil Habit Is Wrecking Its Future | Niko Block

“Ottawa’s aversion to risk on industrial policy appears stronger than ever — despite growing pressure for change. Over the past twenty-odd years, Canadian governments have occasionally expressed real interest in a green transition, but their capacity to deliver was constrained by the North American Free Trade Agreement’s (NAFTA) limits on state support for renewables. In the meantime, the oil and gas sector has only grown in size and political clout. Since NAFTA’s renegotiation under Trump’s first term, some policy space has opened up. But the oil-driven price shock of the past few years has made governments more nervous than ever about restraining fossil fuel production. The ironic result is that policymakers now have more room to act — but less will to do so.

Our current circumstance presents a new variation of a long-standing problem: weak manufacturing capacity and a deep reliance on resource extraction. In some respects, this resembles the resource curse — the pattern in which resource-rich countries underinvest in other sectors — but with distinct Canadian characteristics.

From the mid to late twentieth century, Canada moved away from primary product dependency and developed a modest manufacturing base for higher-value finished products, though much of it was built with the backing of US capital. Since 2000, however, much of that progress has been reversed by the rise of Canada’s export-oriented carbon sector. As a result, Canadian policymakers now confront a double bind: diminished capacity in innovative industries and heavy reliance on fossil fuel production, especially in Alberta and Saskatchewan. […]

This is all to say nothing of the damage the oil sands are doing to the planet, the scale of which is difficult to fathom. The industry has long acknowledged that a barrel of Albertan oil is more polluting than conventional oil, but its own estimates consistently understate the problem. One mind-bending study published last year in Science found that total emissions from the oil sands appear to be 19 to 63 times larger than the industry-reported values.

Yet despite years of warning from the scientific community, Ottawa has no plan to mitigate this catastrophe.”

2. The life of a dairy cow | Marina Bolotnikova & Cat Willett

I have yet to hear a single compelling reason that justifies humanity’s ongoing consumption of cows’ milk. Scaling dairy production is impossible without scaling cruelty. We have the ingenuity to replicate tastes through alternatives and not double down on this barbarism. See the illustrations linked above for a high-level A to Z of one of our collective moral failures.

“Most people in the industry don’t want to hurt animals. But the economics of dairy, and the cows’ commodity status, make it impossible not to.

Dairy depends on mind-boggling levels of waste – a conveyor belt churning through resource-intensive, 1.500-pound mammals as though they were corn husks. It’s a staggeringly inefficient way of producing food, and it also, as shown by this past year’s bird flu outbreaks among dairy cows, poses profound zoonotic disease risks.

A century ago, when nutrition science was crude and agriculture less efficient, investing in intensified dairy production might have looked sensible. Today, even as the myth of cows’ milk as a superfood has been debunked and its ethical problems become apparent, dairy remains shored up by decades of government investment and cultural imagery.”

3. The Climate Movement Should Become a Human Movement | Rhiana Gunn-Wright & Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

“People asking about climate are like, What do we do? Actually, the answer is to be more human. We have to understand that the climate movement’s strength comes from being a moral and a human movement, not exclusively one that is about science and technology. If we’re not strengthening that and proving that all the time, I don’t know where we’ll be, especially at this level of chaos. Nobody’s thinking about climate right now — nobody. One of the new Trump environmental officials is like, Oh, climate change is not even a big problem. It’s not anywhere on the list of big problems. And he’s not the only person who thinks that.

The climate movement, despite growing internationally and in the U.S., is still largely funded and run by white people. And white men in particular. In the Biden administration, you saw a real retraction away from Green New Deal–esque appeals to thinking about climate as a bigger issue. In some ways, the Green New Deal was an emotional appeal. How do you feel about the world? What kind of life do you want? How can we use climate to get there? We sort of moved away from that. And the conversations became technical. […]

The answer is not giving people more facts. And we can’t appeal only to fear and anger as emotions. Clearly, climate freaks people out. Even natural disasters don’t freak people out as much. Because, again, people aren’t experiencing it themselves; they’re experiencing it mediated through media. So once the news cycle moves on, people move on, too, unless they were directly affected. That leaves us to figure out how we as a movement slice through that and how we craft the issue to move forward, because we have to be honest about it. All of this is about crafting issues. Policy has never, ever been only about truth and facts. Ever. You are always constructing a narrative in order to essentially wage battle within a particular context, and we have to get comfortable with that. There’s a difference between doing that and misinformation. At the end of the day, this is not a fucking science fair. No one’s coming to pin a ribbon on the person with the best graphs.”

4. Fertility on demand | Ruxandra Teslo

“The gender pay gap has barely changed since the early 2000s. In the US women who work full time earn 84 percent of what men earn. Twenty years ago they earned 80 percent. One of the main reasons for this is that women spend a lot of time bearing and caring for children, especially during their early years. This work provides significant public benefit, but it comes at a private cost: women’s wages drop after giving birth and never fully recover.

Women know this gap exists and plan accordingly: in countries where the motherhood penalty is keenest, the birth rate is lower.

Governments have worked to address gender pay gaps by introducing maternity and paternity leave, creating preschool programs, providing tax benefits to parents, and more. These policies have helped, but they are limited in what they can achieve so long as women continue to have children during the years most critical to their careers.

Taking time out of the workforce to bear and raise children while in their twenties and thirties means women have less time to accumulate the network, skills, and experience necessary to rise to the top of their fields. The later women wait to have their first child, the more they earn.

But unfortunately, women’s fertility falls with age. If women wait until they are 40 to have children, they can probably achieve the career they want, but they are unlikely to have as many children as they would like – and they may not be able to have children at all. How to manage this tradeoff is a pressing question for any woman in the modern world. But emerging technology may solve this problem.

In fact, this may be a unique few decades of history where women have the option to choose professional accomplishment but risk (unwanted) childlessness as a price. New technology may soon allow women to maintain their fertility into their forties and fifties, giving them the same options that men have.”

5. Anatomy of an Extinction | Jackie Flynn Mogensen

“Late in September, as Hurricane Helene struck the Southeast, Wally Smith immediately thought of the salamanders. Of course, he fretted over the safety of his parents, brother, and extended family in the path of the storm in the north Georgia mountains, but he couldn’t help but worry about the amphibians in harm’s way, too. As a conservation biologist and herpetologist at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise, salamanders are his life’s work, particularly at-risk species. Most recently, that includes one elusive giant salamander: the Eastern hellbender. The storm threatened to damage the rivers it inhabits. Even if the hellbenders survived, he recalls thinking, was there a place they could go?

Serious floods are nothing new for Appalachia. But more frequent and severe storms, worsened by climate change, have heightened scientists’ concerns about animals like the Eastern hellbender, which already are facing threats from human development and are less able to bounce back after natural disasters. Even before Helene, researchers estimated that hellbenders have disappeared from around 90 percent of their original habitat.

Natural disasters—say, floods in the Northeast, saltwater intrusion in the Mississippi River, or wildfires in Los Angeles—can be catastrophic for a vulnerable species already on the path to obsolescence. […]

Helene ended up being among the costliest hurricanes in US history, killing more than 200 people and causing an estimated $78.7 billion in damage. The environment took a hit, too. Migratory birds got thrown off course. An estimated 822,000 acres of forest in North Carolina were mangled. Streams, home to freshwater mussels that live nowhere else on Earth, eroded.

And then there’s the hellbenders: flushed from rock cavities, tossed from rivers, squashed by debris. […]

At a certain point, it won’t take much to knock out the hellbender. If you were to line up every species on Earth in the order of most to least at risk of extinction, explains John Wiens, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, those in the front likely would be geographically isolated species, the ones with low numbers, or the species that are unable to travel. (This is, in part, why the vast majority of modern extinctions have been species living on islands, he notes.) Things like disease, invasive species, or land development can also make an already endangered species that much more vulnerable to climate events. Across the world, an estimated 41 percent of amphibians—more than any other animal class—are threatened by extinction, in part because of the effects of climate change. […]

Toward the end of my trip, I couldn’t shake the feeling of how completely Helene reshaped, well, everything in North Carolina and Virginia. It wasn’t just the tragedy of lost lives or generational homes gone forever. It wasn’t only the uprooted trees or reshaped streams or all the animals hunkered within them. It was the smallest of things, too: as one survivor put it, like the loss of a favorite restaurant, a shift in the day-to-day work of a biologist, or, for a hellbender, perhaps the loss of a familiar river boulder.

As Smith sees it, hellbenders and humans are different chapters of the same story. Climate change, after all, doesn’t discriminate between species—it’s coming for all of us.”

6. Borders May Change, But People Remain | Emiliano Aguilar

““History can either oppress or liberate a people,” Rodolfo Acuña, the founder of Chicana and Chicano Studies at California State University Northridge, proclaimed in the opening line to his 1972 classic, Occupied America: The Chicano’s Struggle Toward Liberation. Writing in the throes of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, or El Movimiento, Acuña argued that “Mexicans in the United States are still a colonized people, but now the colonization is internal—it is occurring within the country rather than being imposed by an external power.” The remembrance of conflict informed Acuña’s internal colonization theory, which defined his seminal text. Since the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), which ended the Mexican-American War, the colonization of Chicanos was one within borders instead of outside of them.

Simply, memories matter—for history and the people who invoke them. The act of remembrance is more than just nostalgia or an individual recollection of the past. Beyond our personal experiences, we create and contribute to collective memories, which are influenced by learning about the past from our families and friends and, in turn, share those memories with others. Each generation remembers and invokes aspects of the past to their present. Memories encapsulate the contested visions of history. Historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage reminds us that memories involve the “active labor of selecting, structuring, and imposing meaning on the past.” In choosing to remember certain events at specific times, seemingly uncontroversial facts become subjects of politicization. Collective remembrance illustrates the opportunity to build awareness. As Acuña contended, “Awareness will help us take action against the forces that oppress not only Chicanos but the oppressor himself.” Central to this awareness becomes the act of remembering, or “refusing to forget,” the past injustices against Mexican Americans in the aftermath of the Mexican-American War. In the case of the generations of Mexican Americans in the decades after the conflict, this awareness was tied to offering alternative views of the conflict.

Historically, Valerio-Jiménez unravels how scholars, journalists, and activists “deployed collective war memories in varied and often contradictory ways to push their political agendas.” While the physical consequences of the war’s aftermath lessened and became less prominent after the initial generation, the influences remained in the second-class citizenship that defined Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest. While Valerio-Jiménez utilizes the book’s first chapter to summarize the events leading to the Mexican-American War, the negotiations surrounding the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and the immediate aftermath of the conflict, the following five chapters proceed chronologically across approximately 30 years each. How, then, did Mexican Americans still utilize the event, even as time granted them distance from the traumatic conflict?”

7. Second Nature | Rafaël Newman

“Our house religion was social democracy.

Our family commitment to sexual and racial equality, socialized medicine, decolonization, and government regulation of the market was manifest, of course, in a geographically and historically conditioned form: in electoral loyalty to the NDP, Canada’s mainstream progressive party, founded in 1932 as the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and renamed the New Democratic Party in 1961. Our family credo held that the Liberal Party of Canada, known as the Grits, might look progressive enough, but their instincts would always be pro-business; any socially progressive policies they may have championed had been forced on them by their marriages of parliamentary convenience with the New Democrats. As for the Tories, Canada’s Conservatives, they were simply out of the question for progressives: it’s in the name. My choice of the NDP in the ballot box, when I came of voting age, was thus at once more, and less, than a deliberate commitment: it was a reflex, almost an instinct. It was second nature. […]

It wasn’t long, however, before our allegiance to the common faith was tested, when we were confronted with the contradictions of political affiliation, the notorious strange bed-fellows created by common travail. Barely pulled away from the curb, our driver revealed himself to be an advocate of the “socialism of fools” as he began to rail against the alleged Jewish cabal behind Pierre Trudeau, then still Liberal prime minister of Canada. Adam and I were silent, struggling inwardly with the need to protest his outrageous antisemitism but cowed by the man’s seniority, ashamed of our own craven inhibition and terrified that our diffidence would be understood as complicity by our vicious companion. Perhaps, too, we were discomfited by an absurd and secret fear: that there was some truth in the conspiracy theory. […]

It does feel like the rise of rightwing extremism, around the world and especially in the US, is frightening progressive voters (those who have not yet been alienated by divisions on the left over Gaza or Ukraine) into a closer compromise with otherwise anathema centrists. Jagmeet Singh, the leader of the federal New Democrats, is judged to have fared well enough in the recent leadership debates among the four major parties (the Grits, the Tories, the NDP, and the Bloc Québécois, a regional party which, like the Bavarian CSU in Germany, absurdly runs for federal office)—but Singh’s insistence on the importance of preserving and expanding Canada’s socialized healthcare system is widely accounted a parochial distraction from the “grave existential threat” of tariffs and invasion. And in any case, the idea of sending a youngish, turbaned career politician of color to “negotiate” with Trump and his coterie of hyenas, rather than an older, more conventionally attired, WASPy central banker, evidently strikes fear into the hearts of the most committed Canadian social democrats.

But who can say what is the best progressive approach to the present American regime, whose hideous character is still in the process of revealing itself?”

8. What the Election Won’t Fix | Paul Wells

“I think Canada’s politics have sunk into deep ruts. I think we need fresh and serious thinking about what kind of country we want to be. I worry that euphoria after an election in the winning camp, followed immediately by the crush of events, risks preempting fresh approaches.

For a decade, our political parties, our Parliament, our public service, and the other institutions of our democracy have been putting more and more energy into forgetting how to make decisions. Instead, they’re all in for message amplification. They’re so busy saying that they don’t hear—don’t, in fact, dare to hear because new information would only complicate lives they barely control. There’s a forced, hollow certainty to too much of our political discourse that barely masks timidity and confusion behind.

Our leaders are horrified at the prospect of being disagreed with, a phobia exemplified by the deepening moral cowardice of Pierre Poilievre in the face of the most routine journalistic inquiry. But I see Poilievre as an increasingly pathetic symptom of a widespread phobia, rather than as a particular instigator. After all, a prominent unperson, whose decade-long tenure as prime minister we are now asked to forget, spent last summer popping up unannounced, each time in the presence of a single reporter who was formally forbidden from asking him any questions.

Sorry, I just said something mean about your favourite leader, everyone. But that’s a big part of the problem. We’re building cults of personality around people with unremarkable personalities. In a polarized age, supporters of our hollow parties have been betting everything on a succession of unpersuasive leaders, and investing not nearly enough in the institutions that would help us navigate wild times, if we let them.”